Getting Started with SBOL¶

This beginner’s guide introduces the basic principles of pySBOL for new users. Most of the examples discussed in this guide are excerpted from the example script. The objective of this documentation is to familiarize users with the basic patterns of the API. For more comprehensive documentation about the API, refer to documentation about specific classes and methods.

The class structure and data model for the API is based on the Synthetic Biology Open Language. For more detail about the SBOL standard, visit sbolstandard.org or refer to the specification document. This document provides diagrams and description of all the standard classes and properties that comprise SBOL.

Creating an SBOL Document¶

In a previous era, engineers might sit at a drafting board and draft a design by hand. The engineer’s drafting sheet in pySBOL is called a Document. The Document serves as a container, initially empty, for SBOL data objects which represent elements of a biological design. Usually the first step is to construct a Document in which to put your objects. All file I/O operations are performed on the Document. The read and write methods are used for reading and writing files in SBOL format.

>>> doc = Document()

>>> doc.read('crispr_example.xml')

>>> doc.write('crispr_example_out.xml')

Reading a Document will wipe any existing contents clean before import. However, you can import objects from multiple files into a single Document object using Document.append(). This can be advantageous when you want to integrate multiple objects from different files into a single design. This kind of data integration is an important and useful feature of SBOL.

A Document may contain different types of SBOL objects, including ComponentDefinitions, ModuleDefinitions, Sequences, and Models. These objects are collectively referred to as TopLevel objects because they can be referenced directly from a Document. The total count of objects contained in a Document is determined using the len function. To view an inventory of objects contained in the Document, simply print it.

>>> len(doc)

31

>>> print(doc)

Attachment....................0

Collection....................0

CombinatorialDerivation.......0

ComponentDefinition...........25

Implementation................0

Model.........................0

ModuleDefinition..............2

Sequence......................4

Analysis......................0

Build.........................0

Design........................0

SampleRoster..................0

Test..........................0

Activity......................0

Agent.........................0

Plan..........................0

Annotation Objects............0

---

Total.........................31

Each SBOL object in a Document is uniquely identified by a special string of characters called a Uniform Resource Identifier (URI). A URI is used as a key to retrieve objects from the Document. To see the identities of objects in a Document, iterate over them using a Python iterator.

>>> for obj in doc:

... print(obj)

...

http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example/mKate_seq/1.0.0

http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example/gRNA_b_nc/1.0.0

http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example/mKate_cds/1.0.0

.

.

These objects are sorted into object stores based on the type of object. For example to view ComponentDefinition objects specifically, iterate through the Document.componentDefinitions store:

Similarly, you can iterate through Document.moduleDefinitions, Document.sequences, Document.models, or any top level object. The last type of object, Annotation Objects is a special case which will be discussed later.

These URIs are said to be sbol-compliant. An sbol-compliant URI consists of a scheme, a namespace, a local identifier (also called a displayId), and a version number. In this tutorial, we use URIs of the type http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example/my_obj/1.0.0.0, where the scheme is indicated by http://, the namespace is http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example, the local identifier is my_object, and the version is 1.0.0. SBOL-compliant URIs enable shortcuts that make the pySBOL API easier to use and are enabled by default. However, users are not required to use sbol-compliant URIs if they don’t want to, and this option can be turned off.

Based on our inspection of objects contained in the Document above, we can see that these objects were all created in the namespace http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example. Thus, in order to take advantage of SBOL-compliant URIs, we set an environment variable that configures this namespace as the default. In addition we set some other configuration options.

>>> setHomespace('http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example')

Setting the Homespace has several advantages. It simplifies object creation and retrieval from Documents. In addition, it serves as a way for a user to claim ownership of new objects. Generally users will want to specify a Homespace that corresponds to their organization’s web domain.

Creating SBOL Data Objects¶

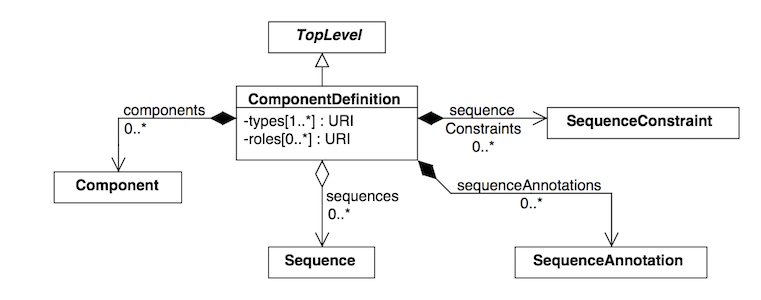

Biological designs can be described with SBOL data objects, including both structural and functional features. The principle classes for describing the structure and primary sequence of a design are ComponentDefinitions, Components, Sequences, and SequenceAnnotations. The principle classes for describing the function of a design are ModuleDefinitions, Modules, Interactions, and Participations. Other classes such as Design, Build, Test, Analysis, Activity, and Plan are used for managing workflows.

In the official SBOL specification document, classes and their properties are represented as box diagrams. Each box represents an SBOL class and its attributes. Following is an example of the diagram for the ComponentDefinition class which will be referred to in later sections. These class diagrams follow conventions of the Unified Modeling Language.

As introduced in the previous section, SBOL objects are identified by a uniform resource identifier (URI). When a new object is constructed, the user must assign a unique identity. The identity is ALWAYS the first argument supplied to the constructor of an SBOL object. Depending on which configuration options for pySBOL are specified, different algorithms are applied to form the complete URI of the object. The following examples illustrate these different configuration options.

The first set of configuration options demonstrates ‘open-world’ mode, which means that URIs are explicitly specified in full by the user, and the user is free to use whatever convention or conventions they want to form URIs. Open-world configuration can be useful sometimes when integrating data objects derived from multiple files or web resources, because it makes no assumptions about the format of URIs.

>>> setHomespace('')

>>> Config.setOption('sbol_compliant_uris', False)

>>> Config.setOption('sbol_typed_uris', False)

>>> crispr_template = ModuleDefinition('http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example/CRISPR_Template')

>>> print(crispr_template)

http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example/CRISPR_Template

The second set of configuration options demonstrates use of a default namespace for constructing URIs. The advantage of this approach is simply that it reduces repetitive typing. Instead of typing the full namespace for a URI every time an object is created, the user simply specifies the local identifier. The local identifier is appended to the namespace. This is a handy shortcut especially when working interactively in the Python interpreter.

>>> setHomespace('http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example/')

>>> Config.setOption('sbol_compliant_uris', False)

>>> Config.setOption('sbol_typed_uris', False)

>>> crispr_template = ModuleDefinition('CRISPR_Template')

>>> print(crispr_template)

http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example/CRISPR_Template

The third set of configuration options demonstrates SBOL-compliant mode. In this example, a version number is appended to the end of the URI. Additionally, when operating in SBOL-compliant mode, the URIs of child objects are algorithmically constructed according to automated rules (not shown here).

>>> setHomespace('http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example/')

>>> Config.setOption('sbol_compliant_uris', True)

>>> Config.setOption('sbol_typed_uris', False)

>>> crispr_template = ModuleDefinition('CRISPR_Template')

>>> print(crispr_template)

http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example/CRISPR_Template/1.0.0

The final example demonstrates typed URIs. When this option is enabled, the type of SBOL object is included in the URI. Typed URIs are useful because sometimes the user may want to re-use the same local identifier for multiple objects. Without typed URIs this may lead to collisions between non-unique URIs. This option is enabled by default, but the example file CRISPR_example.py does not use typed URIs, so for all the examples in this guide this option is assumed to be disabled.

>>> setHomespace('http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example/')

>>> Config.setOption('sbol_compliant_uris', True)

>>> Config.setOption('sbol_typed_uris', True)

>>> crispr_template_md = ModuleDefinition('CRISPR_Template')

>>> print(crispr_template)

http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example/ModuleDefinition/CRISPR_Template/1.0.0

>>> crispr_template_cd = ComponentDefinition('CRISPR_Template')

http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example/ComponentDefinition/CRISPR_Template/1.0.0

Constructors for SBOL objects follow a fairly predictable pattern. The first argument is ALWAYS the identity of the object. Other arguments may follow, depending on in the SBOL class has required attributes. Attributes are required if the specification says they are. In a UML diagram, required fields are indicated as properties with a cardinality of 1 or more. For example, a ComponentDefinition (see the UML diagram above) has only one required field, types, which specifies one or more molecular types for a component. Required fields SHOULD be specified when calling a constructor. If they are not, they will be assigned default values. The following creates a protein component. If the BioPAX term for protein were not specified, then the constructor would create a ComponentDefinition of type BIOPAX_DNA by default.

>>> cas9 = ComponentDefinition('Cas9', BIOPAX_PROTEIN) # Constructs a protein component

>>> target_promoter = ComponentDefinition('target_promoter') # Constructs a DNA component by default

Using Ontology Terms for Attribute Values¶

Notice the ComponentDefinition.types attribute is specified using a predefined constant. The ComponentDefinition.types property is one of many SBOL attributes that uses ontology terms as property values. The ComponentDefinition.types property uses the BioPax ontology <https://bioportal.bioontology.org/ontologies/BP/?p=classes&conceptid=root> to be specific. Ontologies are standardized, machine-readable vocabularies that categorize concepts within a domain of scientific study. The SBOL 2.0 standard unifies many different ontologies into a high-level, object-oriented model.

Ontology terms also take the form of Uniform Resource Identifiers. Many commonly used ontological terms are built-in to pySBOL as predefined constants. If an ontology term is not provided as a built-in constant, its URI can often be found by using an ontology browser tool online. Browse Sequence Ontology terms here <http://www.sequenceontology.org/browser/obob.cgi> ` and `Systems Biology Ontology terms here. While the SBOL specification often recommends particular ontologies and terms to be used for certain attributes, in many cases these are not rigid requirements. The advantage of using a recommended term is that it ensures your data can be interpreted or visualized by other applications that support SBOL. However in many cases an application developer may want to develop their own ontologies to support custom applications within their domain.

The following example illustrates how the URIs for ontology terms can be easily constructed, assuming they are not already part of pySBOL’s built-in ontology constants.

>>> SO_ENGINEERED_FUSION_GENE = SO + '0000288' # Sequence Ontology term

>>> SO_ENGINEERED_FUSION_GENE

'http://identifiers.org/so/SO:0000288'

>>> SBO_DNA_REPLICATION = SBO + '0000204' # Systems Biology Ontology term

>>> SBO_DNA_REPLICATION

'http://identifiers.org/biomodels.sbo/SBO:0000204'

Adding and Getting Objects from a Document¶

In some cases a developer may want to use SBOL objects as intermediate data structures in a computational biology workflow. In this case the user is free to manipulate objects independently of a Document. However, if the user wishes to write out a file with all the information contained in their object, they must first add it to the Document. This is done using add methods. The names of these methods follow a simple pattern, simply “add” followed by the type of object.

>>> doc.addModuleDefinition(crispr_template)

>>> doc.addComponentDefinition(cas9)

Objects can be retrieved from a Document by using get methods. These methods ALWAYS take the object’s full URI as an argument.

>>> crispr_template = doc.getModuleDefinition('http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example/CRISPR_Template/1.0.0')

>>> cas9 = doc.getComponentDefinition('http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example/cas9_generic/1.0.0')

When working interactively in a Python environment, typing long form URIs can be tedious. Operating in SBOL-compliant mode allows the user an alternative means to retrieve objects from a Document using local identifiers.

>>> Config.setOption('sbol_compliant_uris', True)

>>> Config.setOption('sbol_typed_uris', False)

>>> crispr_template = doc.moduleDefinitions['CRISPR_Template']

>>> cas9 = doc.componentDefinitions['cas9_generic']

Getting, Setting, and Editing Attributes¶

The attributes of an SBOL object can be accessed like other Python class objects, with a few special considerations. For example, to get the values of the displayId and identity properties of any object :

Note that displayId gives only the shorthand, local identifier for the object, while the identity property gives the full URI.

The attributes above return singleton values. Some attributes, like ComponentDefinition.roles and ComponentDefinition.types support multiple values. Generally these attributes have plural names. If an attribute supports multiple values, then it will return a list. If the attribute has not been assigned any values, it will return an empty list.

>>> cas9.types

['http://www.biopax.org/release/biopax-level3.owl#Protein']

>>> cas9.roles

[]

Setting an attribute follows the ordinary convention for assigning attribute values:

>>> crispr_template.description = 'This is an abstract, template module'

To set multiple values:

>>> plasmid = ComponentDefinition('pBB1', BIOPAX_DNA, '1.0.0')

>>> plasmid.roles = [ SO_PLASMID, SO_CIRCULAR ]

Although properties such as types and roles behave like Python lists in some ways, beware that list operations like append and extend do not work directly on these kind of attributes, due to the nature of the C++ bindings. If you need to append values to an attribute, use the following idiom:

>>> plasmid.roles = [ SO_PLASMID ]

>>> plasmid.roles = plasmid.roles + [ SO_CIRCULAR ]

To clear all values from an attribute, set to None:

>>> plasmid.roles = None

Creating, Adding and Getting Child Objects¶

Some SBOL objects can be composed into hierarchical parent-child relationships. In the specification diagrams, these relationships are indicated by black diamond arrows. In the UML diagram above, the black diamond indicates that ComponentDefinitions are parents of SequenceAnnotations. Properties of this type can be modified using the add method and passing the child object as the argument.

>>> point_mutation = SequenceAnnotation('PointMutation')

>>> target_promoter.sequenceAnnotations.add(point_mutation)

Alternatively, the create method captures the construction and addition of the SequenceAnnotation in a single function call. The create method ALWAYS takes one argument–the URI of the new object. All other values are initialized with default values. You can change these values after object creation, however.

>>> target_promoter.sequenceAnnotations.create('PointMutation')

Conversely, to obtain a Python reference to the SequenceAnnotation from its identity:

>>> point_mutation = target_promoter.sequenceAnnotations.get('PointMutation')

Or equivalently:

>>> point_mutation = target_promoter.sequenceAnnotations['PointMutation']

Creating and Editing Reference Properties¶

Some SBOL objects point to other objects by way of URI references. For example, ComponentDefinitions point to their corresponding Sequences by way of a URI reference. These kind of properties correspond to white diamond arrows in UML diagrams, as shown in the figure above. Attributes of this type contain the URI of the related object.

>>> eyfp_gene = ComponentDefinition('EYFPGene', BIOPAX_DNA)

>>> seq = Sequence('EYFPSequence', 'atgnnntaa', SBOL_ENCODING_IUPAC)

>>> eyfp_gene.sequence = seq

>>> print (eyfp_gene.sequence)

'http://sbols.org/Sequence/EYFPSequence/1.0.0'

Note that assigning the seq object to the eyfp_gene.sequence actually results in assignment of the object’s URI. An equivalent assignment is as follows:

>>> eyfp_gene.sequence = seq.identity

>>> print (eyfp_gene.sequence)

'http://sbols.org/Sequence/EYFPSequence/1.0.0'

Iterating and Indexing List Properties¶

Some properties can contain multiple values or objects. Additional values can be specified with the add method. In addition you may iterate over lists of objects or values.

# Iterate through objects (black diamond properties in UML)

for p in cas9_complex_formation.participations:

print(p)

print(p.roles)

# Iterate through references (white diamond properties in UML)

for role in reaction_participant.roles:

print(role)

Numerical indexing of lists works as well:

for i_p in range(0, len(cas9_complex_formation.participations)):

print(cas9_complex_formation.participations[i_p])

Searching a Document¶

To see if an object with a given URI is already contained in a Document or other parent object, use the find method. Note that find function returns the target object cast to its base type which is SBOLObject, the generic base class for all SBOL objects. The actual SBOL type of this object, however is ComponentDefinition. If necessary the base class can be downcast using the cast method.

>>> obj = doc.find('http://sbols.org/CRISPR_Example/mKate_gene/1.0.0')

>>> obj

SBOLObject

>>> parseClassName(obj.type)

'ComponentDefinition'

>>> cd = obj.cast(ComponentDefinition)

>>> cd

ComponentDefinition

The find method is probably more useful as a boolean conditional when the user wants to automatically construct URIs for objects and needs to check if the URI is unique or not. If the object is found, find returns an object reference (True), and if the object is not found, it returns None (False). The following code snippet demonstrates a function that automatically generates ComponentDefinitions.

def createNextComponentDefinition(doc, local_id):

i_cdef = 0

cdef_uri = getHomespace() + '/%s_%d/1.0.0' %(local_id, i_cdef)

while doc.find(cdef_uri):

i_cdef += 1

cdef_uri = getHomespace() + '/%s_%d/1.0.0' %(local_id, i_cdef)

doc.componentDefinitions.create('%s_%d' %(local_id, i_cdef))

Copying Documents and Objects¶

Copying a Document can result in a few different ends, depending on the user’s goal. The first option is to create a simple clone of the original Document. This is shown below in which the user is assumed to have already created a Document with a single ComponentDefinition. After copying, the object in the Document clone has the same identity as the object in the original Document.

>>> for o in doc:

... print o

...

http://examples.org/ComponentDefinition/cd/1

>>> doc2 = doc.copy()

>>> for o in doc2:

... print o

...

http://examples.org/ComponentDefinition/cd/1

More commonly a user wants to import objects from the target Document into their Homespace. In this case, the user can specify a target namespace for import. Objects in the original Document that belong to the target namespace are copied into the user’s Homespace. Contrast the example above with the following.

>>> setHomespace('http://sys-bio.org')

>>> doc2 = doc.copy('http://examples.org')

>>> for o in doc:

... print o

...

http://examples.org/ComponentDefinition/cd/1

>>> for o in doc2:

... print o

...

http://sys-bio.org/ComponentDefinition/cd/1

In the examples above, the copy method returns a new Document. However, it is possible to integrate the result of multiple copy operations into an existing Document.

>>> for o in doc1:

print o

http://examples.org/ComponentDefinition/cd1/1

>>> for o in doc2:

print o

...

http://examples.org/ComponentDefinition/cd2/1

>>> doc1.copy('http://examples.org', doc3)

Document

>>> doc2.copy('http://examples.org', doc3)

Document

>>> for o in doc3:

... print o

...

http://examples.org/ComponentDefinition/cd2/1

http://examples.org/ComponentDefinition/cd1/1

Converting To and From Other Sequence Formats¶

It is possible to convert SBOL to and from other common sequence formats. Conversion is performed by calling the online converter tool , so an internet connection is required. Currently the supported formats are SBOL2, SBOL1, FASTA, GenBank, and GFF3. The following example illustrates how to import and export to these different formats. Note that conversion can be lossy.

>>> doc.exportToFormat('GenBank', 'crispr_example_out.gb')

>>> doc.importFromFormat('GenBank', 'crispr_example_out.gb')

Creating Biological Designs¶

This concludes the basic methods for manipulating SBOL data structures. Now that you’re familiar with these basic methods, you are ready to learn about libSBOL’s high-level design interface for synthetic biology. See SBOL Examples.